AES, or Advanced Encryption Standard, is the benchmark symmetric encryption algorithm. But what are the elements that have made it resistant to attacks for over 20 years? It was established by NIST following a competition to find a replacement for DES, which was cracked due to an overly low key size limit. The winner was Rindjael's variant, now known by the acronym AES.

This algorithm consists of five distinct mechanisms: Subbytes, Shiftrows, Mixcolumns, Addroundkey, and Key Schedule. Before going into detail, some prior knowledge is necessary.

First, AES works in a finite field, denoted GF(28). In concrete terms, this means that it works with two values (0 and 1) out of eight elements, or one byte. A finite field requires a modulo in order to remain within the field when an operation exceeds the possible value on one byte. The modulo chosen for AES is x⁸+x⁴+x³+x+1, which will be referred to as the modulo N hereafter.

AES is a block cipher, meaning that each encrypted message/file is divided into 128-bit blocks, which are treated as a 4*4 byte matrix.

The 5 mechanisms

Subbytes

Subbytes consists of two steps:

- Modular inversion of each byte, meaning that each input byte A is replaced by byte B that solves the equation A*B congruent to 1 modulo N

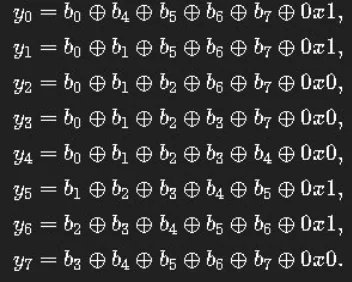

- An affine transformation, also known as five consecutive XOR operations for each bit of each byte with other bits of the same byte, and one bit of a fixed byte

This part introduces non-linearity into AES, i.e., the impossibility of reducing AES encryption to a low-degree equation.

Shiftrows

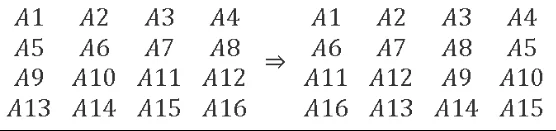

This step simply consists of horizontally rotating the rows of the matrix, with a shift of 0 for the first row, 1 for the second, 2 for the third, and 3 for the fourth, as illustrated in the screenshot below:

Mixcolumns

Mixcolumns consists of taking each column of elements (example with the output of Shiftrows A1,A6,A11,16) and multiplying them by a given, fixed, and publicly known matrix. This step, combined with Shiftrows, ensures that each output byte depends on a maximum number of different input bytes, limiting the appearance of patterns in similar input blocks.

Addroundkey

This step involves including the key in the algorithm, which ensures that only those who possess this key can decrypt the message. The result of the previous steps is XORed with a subkey derived from the main key through the key schedule.Key schedule

Key schedule

The master key is divided into 32-bit “words” denoted by W, so in 4 for a 128-bit key to generate subkeys of a fixed size of 128 bits. As many subkeys are required as there are rounds, i.e., 10 for AES 128, leading to a total of 40 words to be generated.

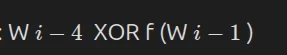

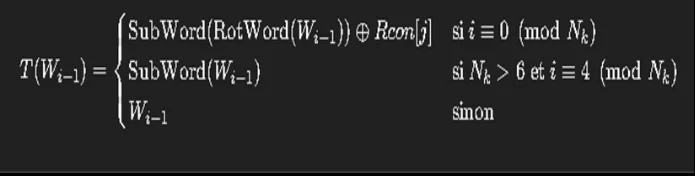

A key word i is defined by:

where f is a function whose definition varies depending on the value of i modulo the number of words in the main key, i.e., 4 for AES 128.

These operations are repeated throughout the rounds, with the exception of round “0” (subbytes + addroundkey) and the last round (Subbytes + Shiftrows + Addroundey). However, seeing that the key is involved late in the algorithm, one might legitimately ask: Are the intermediate steps really that important? We will explore this question with a partial implementation of AES without Subbyte.

Vulnerability

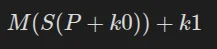

In this implementation without Subbyte, the result of round zero is:

Where P is the plaintext, k0 is the original key, and + is the equivalent of XOR in GF(2⁸) in the first round. Without subbytes, the result is:

Where M corresponds to Mixcolumns, S to Shiftrows, and k1 to the first subkey. This logic applies to each round, without Mixcolumns for the 10th round.

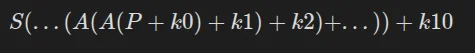

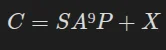

To simplify the final equation, we can set A = MS, which gives us:

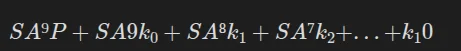

We can expand this equation:

And here, disaster strikes!

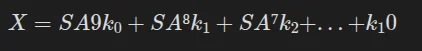

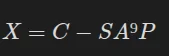

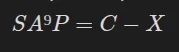

We realize that the plaintext can be isolated from the rest of the equation: if we set:

We can set the equation:  where C is the ciphertext. This also means that:

where C is the ciphertext. This also means that:

However, SA⁹P is NOT dependent on the key, meaning that it can be calculated without knowing it, and X is independent of the plaintext, meaning that if we calculate it once, we can recover any text from the ciphertext:

By “simply” (cough cough) solving SA⁹P

Practical work

For those who have made it this far, congratulations. In order to carry out our little experiment, we need an implementation of AES whose steps are modular. In Python, the best known implementation does not have this flexibility. After various attempts at manual creation (Rule one of cryptography: never implement your own algorithms).

![[images/one_does_not_simply_roll_their_own_crypto.png]]

I discovered that I wasn't the first to look into this issue, and that an implementation that met my needs already existed on GitHub: https://github.com/bozhu/AES-Python/blob/master/aes.py

The following POC is a complete demonstration of the vulnerability, which allows any text to be decrypted from a known plaintext/ciphertext pair. Simply run it in the same folder as the aes.py file mentioned above to execute it:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# chall.py - PoC combining Bo Zhu AES (aes.py) and numpy GF(2) linear algebra

# ------------------------------------------------------------

# This script shows that AES (if you remove the SubBytes step)

# becomes a purely linear cipher, which can be broken using

# linear algebra over GF(2). It constructs matrices that mimic

# AES’s structure and demonstrates full plaintext recovery.

import os

import numpy as np

from aes import AES

# ============================================================

# ---------- GF(2) HELPERS (binary field math) ---------------

# ============================================================

def gf2(a):

"""Force all elements of array a into GF(2) (only 0 or 1)."""

return (np.asarray(a, dtype=np.uint8) & 1)

def gf2_dot(A, B):

"""Matrix multiplication over GF(2): (A @ B) mod 2."""

return gf2((A.astype(np.uint8) @ B.astype(np.uint8)) % 2)

def gf2_add(A, B):

"""Element-wise addition (XOR) over GF(2): (A + B) mod 2."""

return gf2((A.astype(np.uint8) + B.astype(np.uint8)) % 2)

def gf2_eye(n):

"""n×n identity matrix over GF(2). Acts as the '1' for matrix multiplication."""

return gf2(np.identity(n, dtype=np.uint8))

def block_matrix(blocks):

"""Combine small block matrices into one large matrix."""

rows = [np.hstack(row) for row in blocks]

return gf2(np.vstack(rows))

def gf2_mat_pow(A, e):

"""Exponentiate matrix A to power e over GF(2) using repeated squaring."""

assert A.shape[0] == A.shape[1]

n = A.shape[0]

result = gf2_eye(n)

base = A.copy()

while e > 0:

if e & 1:

result = gf2_dot(result, base)

base = gf2_dot(base, base)

e >>= 1

return result

def gf2_mat_inv(A):

"""

Compute the inverse of a square matrix A over GF(2)

using Gaussian elimination (mod 2).

"""

A = gf2(A.copy())

n = A.shape[0]

assert A.shape[0] == A.shape[1]

aug = np.hstack([A.astype(np.uint8), gf2_eye(n).astype(np.uint8)])

row = 0

for col in range(n):

pivot = None

for r in range(row, n):

if aug[r, col] == 1:

pivot = r

break

if pivot is None:

raise np.linalg.LinAlgError("Matrix is singular in GF(2)")

if pivot != row:

aug[[pivot, row]] = aug[[row, pivot]]

for r in range(n):

if r != row and aug[r, col] == 1:

aug[r, :] ^= aug[row, :]

row += 1

if row == n:

break

inv = aug[:, n:]

return gf2(inv)

# ============================================================

# ---------- CONVERSION HELPERS -------------------------------

# ============================================================

def bytes2mat(b):

"""

Convert 16 bytes -> 1x128 row vector (np.uint8) of bits.

Example: b'AB' -> [0,1,0,0,0,0,0,1, 0,1,0,0,0,0,1,0]

"""

if not isinstance(b, (bytes, bytearray)):

raise TypeError("bytes2mat expects bytes input")

bits = []

for i in b:

tmp = format(i, "08b")

bits.extend(int(ch) for ch in tmp)

arr = np.array(bits, dtype=np.uint8).reshape(1, -1)

return gf2(arr)

def mat2bytes(m):

"""

Convert 1x128 or 128x1 bit matrix -> 16-byte value.

Reverse of bytes2mat.

"""

m = np.asarray(m, dtype=np.uint8)

if m.shape == (128, 1):

row = m[:, 0]

elif m.shape == (1, 128):

row = m[0, :]

else:

row = m.flatten()

if row.size != 128:

raise ValueError("matrix must represent 128 bits")

bits = ''.join(str(int(x)) for x in row)

bytes_list = [int(bits[i:i+8], 2) for i in range(0, 128, 8)]

return bytes(bytes_list)

# ============================================================

# ---------- MATRIX CONSTRUCTION (AES-LIKE STRUCTURE) ---------

# ============================================================

# Build 8x8 identity matrix

I = gf2_eye(8)

# Build X: an 8x8 shift matrix with feedback taps (like an LFSR)

X = gf2(np.zeros((8, 8), dtype=np.uint8))

for i in range(7):

X[i, i+1] = 1

X[3, 0] = 1

X[4, 0] = 1

X[6, 0] = 1

X[7, 0] = 1

# Combine blocks to form 32x32 matrix C (simulating AES MixColumns)

C = block_matrix([

[X, gf2_add(X, I), I, I],

[I, X, gf2_add(X, I), I],

[I, I, X, gf2_add(X, I)],

[gf2_add(X, I), I, I, X]

])

# Zero matrices for building larger block matrices

zeros = gf2(np.zeros((8, 8), dtype=np.uint8))

zeros2 = gf2(np.zeros((32, 32), dtype=np.uint8))

# One-hot block selectors for permutation S

o0 = block_matrix([[I, zeros, zeros, zeros],

[zeros, zeros, zeros, zeros],

[zeros, zeros, zeros, zeros],

[zeros, zeros, zeros, zeros]])

o1 = block_matrix([[zeros, zeros, zeros, zeros],

[zeros, I, zeros, zeros],

[zeros, zeros, zeros, zeros],

[zeros, zeros, zeros, zeros]])

o2 = block_matrix([[zeros, zeros, zeros, zeros],

[zeros, zeros, zeros, zeros],

[zeros, zeros, I, zeros],

[zeros, zeros, zeros, zeros]])

o3 = block_matrix([[zeros, zeros, zeros, zeros],

[zeros, zeros, zeros, zeros],

[zeros, zeros, zeros, zeros],

[zeros, zeros, zeros, I]])

# Build permutation matrix S (cyclically shifts 4 blocks)

S = block_matrix([

[o0, o1, o2, o3],

[o3, o0, o1, o2],

[o2, o3, o0, o1],

[o1, o2, o3, o0]

])

# Build M: block-diagonal repetition of C (4x)

M = block_matrix([

[C, zeros2, zeros2, zeros2],

[zeros2, C, zeros2, zeros2],

[zeros2, zeros2, C, zeros2],

[zeros2, zeros2, zeros2, C]

])

# Combine them into full 128x128 linear layer

R = gf2_dot(M, S) # one round

R9 = gf2_mat_pow(R, 9) # apply 9 rounds

A = gf2_dot(S, R9) # final transformation

# ============================================================

# ---------- AES USAGE (with disabled S-box) -----------------

# ============================================================

do_nothing = lambda *x: None

# Create AES with random key (integer format)

key_int = int.from_bytes(os.urandom(16), byteorder="big")

c = AES(key_int)

# Disable SubBytes (nonlinear part) -> makes AES fully linear!

setattr(c, "_AES__sub_bytes", lambda s: None)

# Prepare plaintexts (two 16-byte examples)

p_bytes = b"Very secret text" # unknown plaintext

p_int = int.from_bytes(p_bytes, "big")

ct_int = c.encrypt(p_int)

ct_bytes = ct_int.to_bytes(16, "big")

p2_bytes = b"Known plaintextt" # known plaintext (for attack)

p2_int = int.from_bytes(p2_bytes, "big")

ct2_int = c.encrypt(p2_int)

ct2_bytes = ct2_int.to_bytes(16, "big")

# ============================================================

# ---------- LINEAR ATTACK / PLAINTEXT RECOVERY ---------------

# ============================================================

# Convert plaintexts and ciphertexts to GF(2) column vectors

p2_col = bytes2mat(p2_bytes).T

ct2_col = bytes2mat(ct2_bytes).T

# Compute constant offset K = ct2 - A*p2 (in GF(2), - == +)

A_p2 = gf2_dot(A, p2_col)

K = gf2_add(ct2_col, A_p2)

# Recover unknown plaintext: p = A⁻¹ * (ct - K)

ct_col = bytes2mat(ct_bytes).T

inner = gf2_add(ct_col, K)

Ainv = gf2_mat_inv(A)

res_col = gf2_dot(Ainv, inner)

recovered_plaintext = mat2bytes(res_col.T)

# ============================================================

# ---------- RESULTS ------------------------------------------

# ============================================================

print("original plaintext :", p_bytes)

print("recovered plaintext :", recovered_plaintext)

print("match:", recovered_plaintext == p_bytes)

Beyond the rather brief output, the core of the logic is here:

R = gf2_dot(M, S) # Round 1

R9 = gf2_mat_pow(R, 9) # 9 following rounds

A = gf2_dot(S, R9) # last round resulting in SA⁹

p2_row = bytes2mat(p2_bytes) # 1 x 128

p2_col = p2_row.T # 128 x 1

ct2_row = bytes2mat(ct2_bytes)

ct2_col = ct2_row.T

A_p2 = gf2_dot(A, p2_col)

X = gf2_add(ct2_col, A_p2)

“A” In the demonstration corresponds to SA⁹ and p2_col to the known plaintext P. By subtracting the value of the ciphertext from this sum, we obtain X, the constant part generated by the introduction of Addroundkey. Once this value has been obtained, we simply take the ciphertext of a secret text and subtract X from it to find SA⁹P_secret.

ct_col = bytes2mat(ct_bytes).T # 128 x 1

inner = gf2_add(ct_col, X) # ct - X

Then simply multiply the result by the inverse of A (=SA⁹) to obtain the secret text in plain text.

Ainv = gf2_mat_inv(A)

res_col = gf2_dot(Ainv, inner) # multiplication by the inverse of A, retrieving the secret cleartext

res_row = res_col.T

recovered_plaintext = mat2bytes(res_row)

This POC is limited to a flag of exactly 16 characters, as it does not implement padding or multiple block handling, but the exploitation logic would remain the same, with the same default value for X.